Summer: Japan's Ghost Season

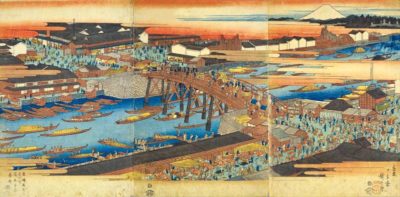

If there’s one thing Tokyoites love, it’s ghost stories. With the popularity of “ukiyo-e” (woodblock prints), rakugo and kabuki theatre in the 1800s, ghost stories or “kaidan”, became a key part of popular culture across Japan, and the arts scene in Tokyo became a hub for sharing them. Despite their often chilling or gruesome nature, adaptations of kaidan were a hit with the masses due to the familiarity of the original stories amongst Japanese people. Because of this, Kaidan are also a staple in the Japanese custom of “noryo”, the idea of enjoying the sweltering summers by stimulating the five senses to cool down, and since the days of Edo, Tokyoites have certainly had the coolest summers.

If there’s one thing Tokyoites love, it’s ghost stories. With the popularity of “ukiyo-e” (woodblock prints), rakugo and kabuki theatre in the 1800s, ghost stories or “kaidan”, became a key part of popular culture across Japan, and the arts scene in Tokyo became a hub for sharing them. Despite their often chilling or gruesome nature, adaptations of kaidan were a hit with the masses due to the familiarity of the original stories amongst Japanese people. Because of this, Kaidan are also a staple in the Japanese custom of “noryo”, the idea of enjoying the sweltering summers by stimulating the five senses to cool down, and since the days of Edo, Tokyoites have certainly had the coolest summers.

Ghost in Kabuki

Kabuki theater is undeniably one of the greatest ways to experience kaidan. Many famous kaidan are set in Tokyo, and their kabuki adaptations have been entertaining audiences all over Japan for centuries. Undeniably the most famous ghost story in Japan, Tokaido Yotsuya Kaidan, often shortened to Yotsuya Kaidan, tells the story of Oiwa, a woman who committed suicide after becoming disfigured from a poison disguised as face cream, which she of course received from her husband’s lover. As a ghost, Oiwa relentlessly haunts her husband, causing him to accidentally murder his new wife and her family, after which he promptly goes insane. Yotsuya Kaidan, as the name suggests, is set in the Yotsuya area of Tokyo, and the original Oiwa is supposedly buried in a graveyard in the nearby Sugamo area. Another popular kabuki play set in Tokyo is Sumidagawa Gonichi no Omokage, commonly known as Hokaibo, which is of course set around Asakusa’s Sumida River. Hokaibo follows the story of a lustful and greedy monk named Hokaibo who, after a series of misdeeds including theft, kidnap and murder, is eventually killed and comes back as an androgynous ghost to haunt Okumi, the target of his affections. Hokaibo is surprisingly a black comedy, and despite being utterly evil, its titular characters is one of the most popular characters in Kabuki theatre today.

Ghost in Rakugo

Rakugo is a more minimalistic style of theater compared to Kabuki, and usually involves a single story-teller seated centre-stage using a fan, a hand towel, and his voice to entertain the audience. One famous storyteller, Sanyutei Encho, shook Edo audiences with renditions of both traditional and original ghost stories. Many of Encho’s rakugo were also adapted into popular kabuki plays, and to this day are a staple of both rakugo and kabuki performances. Out of his original works, both Kaidan Chibusa Enoki and Shinkei Kasanegafuchi are set in Tokyo, in the Itabashi and the Nezu/Yanaka areas respectively. In one of the most recent versions of Kaidan Chibusa Enoki, a famous artist by the name of Shigenobu is tricked and murdered by the villain Sasashige, who then proceeds to take Shigenobu’s wife for his own. Shigenobu then returns as a ghost and saves his child, Mayotaro, from being murdered by Sasashige, who eventually grows up and avenges Shigenobu.

Encho also adapted the infamous Kaidan Botan Doro into a rakugo, which was in turn used as the basis for its kabuki adaptations. Botan Doro is one of the more romantic stories of Encho’s kaidan repertoire, and follows the story of the reunited lovers, Shinzaburo and Otsuyu, who fell in love at first sight, but were soon separated after Shinzaburo heard Otsuyu had died. Not long after this, the heartbroken Shinzaburo is visited by Otsuyu, who claims to have not died at all. Botan Doro is also one of the most shocking stories, as it turns out Otsuyu is dead, and is using her otherwordly powers to hide her corpse-like appearance from Shinzaburo.

Looking at the above, it can be seen that most kaidan are stories of revenge or karmic retribution, but each have wildly different plots, characters and ways that they can be told, making them an exciting way to discover Japanese culture. In Tokyo, theatres such as the Kabukiza Theatre offer English headsets that provide translations of the dialogue as well as important background information relevant to the play. While English Rakugo is less common, events are frequently held by rakugo enthusiasts in Tokyo, especially during the summer months.

Superstitious Spots

It is well-known within kabuki and rakugo circles that actors performing kaidan should tread carefully. In example, actors and theatre staff preparing to perform Yotsuya Kaidan visit Myogyoji Temple, Younji Temple and Oiwa Inari Tamiya Shrine pre-performance to pray away any bad omens, with some even visiting her grave. While this may seem excessive, there are many reports of ill-fated kaidan productions, including an incident in 1919 where the two main actors in a performance of Botan Doro became sick and died within a week of each other. While such occurrences could just be unfortunate coincidences, it never hurts to be careful.

The Burial Mound of Taira no Masakado

In 940AD, a warlord named Taira no Masakado decided he was sick of the government and declared himself the “new” emperor of Japan. The “old” emperor was not pleased with this, and Masakado was subsequently beheaded. His head was displayed at various places across Japan, and ominously brought misfortune to those near it. Now, Masakado’s head is enshrined in a burial mound in Otemachi, Tokyo.

Younji Temple

Along with Oiwa Inari Tamiya Shrine, Younji Temple is dedicated to the famous yurei Oiwa. Younji Temple is also a place where, almost ironically, one can pray for all things marriage-related, which hopefully will put Oiwa’s vengeful spirit to rest after the ill-fated marriage that led to her death.

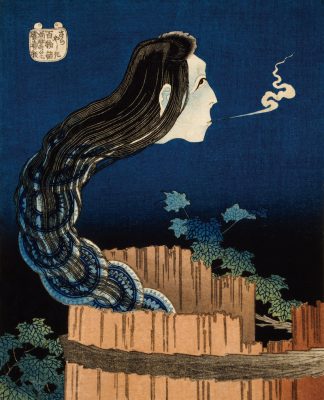

The Tomb and Well of Okiku

Despite being thought of as a fictitious figure, Okiku from Bancho Sarayashiki has her own tomb and well in Tokyo. Not much is known about the history of these sites, but the tomb is rumoured to be in a temple that was originally close to the Bancho area. While the well remains a mystery, it has been the inspiration for many ukiyo-e, including Katsushika Hokusai’s famous 1831 print..

Kanda Myojin Shrine

Remember Taira no Masakado? Well after his death he became a god of sorts, and this shrine is dedicated to him, along with Daikokuten, the god of fortune, and Ebisu, the god of fisheries and business. It is said the shogun Ieyasu Tokugawa used to pay his respects at this shrine during the Edo period, making it one of the most well-known shrines in Tokyo.

0

0