In the world of the Japanese theater, Nohgaku (Noh and Kyogen), Kabuki, and Bunraku have each been recognized by UNESCO as a World Intangible Cultural Heritage. To discover how these beloved forms of Japanese theater originated and rose to fame during the Edo period, WAttention met with Professor Ryuichi Kodama of the Faculty of Letters, Arts and Sciences at Waseda University. Additionally, he is the Vice Director of the Tsubouchi Memorial Theatre Museum. Professor Kodama is an expert in the fields of Theater Studies and History of Performing Arts. Over the years he has gained extensive knowledge of Kabuki theater.

Nohgaku (Noh and Kyogen) arose from the Muromachi period (1333-1573). In summary, Noh was a spiritual drama that used masks and focused on phantasmal or mythical themes. On the other hand, Kyogen, the comical interlude to Noh, did not use masks in most cases. It aimed to arouse laughter in plays depicting more contemporary settings.

Professor Kodama explained that “the word Kabuki, which literally translates into the words “song,” “dance,” and “skill,” first appeared in literature in 1603 when the Edo Shogunate was established. In addition, Style of Bunraku (ningyo joruri) also contributed to the culture in the 1600s. This proves that Bunraku and Kabuki originated in the Edo period (1603-1868). Style of Bunraku comes from a long history of puppets and narratives performed with music from the shamisen (a three-stringed traditional Japanese musical instrument).”

Who were the patrons of the Edo theater scene?

During the Muromachi period, Nohgaku was generally popular among the commoners. However, it was Noh that grew to be the samurai’s source of ceremonial entertainment with the arrival of the Edo period. In fact, to adopt the samurai experience, it was common for the wealthy townsfolk’s sons to learn Noh. Although, unlike today, Noh during those times did not charge admission fees. It was a special performance held for warriors at places such as the Edo Castle, a daimyo’s (warlord) residence.

On certain occasions, ordinary people were welcome to see Noh, which was called “Machi-iri Noh,”. But since it was usually harder for commoners to see Noh performances, the more accessible Bunraku and Kabuki became the favorites of the lower classes. Professor Kodama added, “Different kinds of theater from different eras coexisted with one another, accumulating as time progressed – this is what makes Japanese theater history so fascinating.”

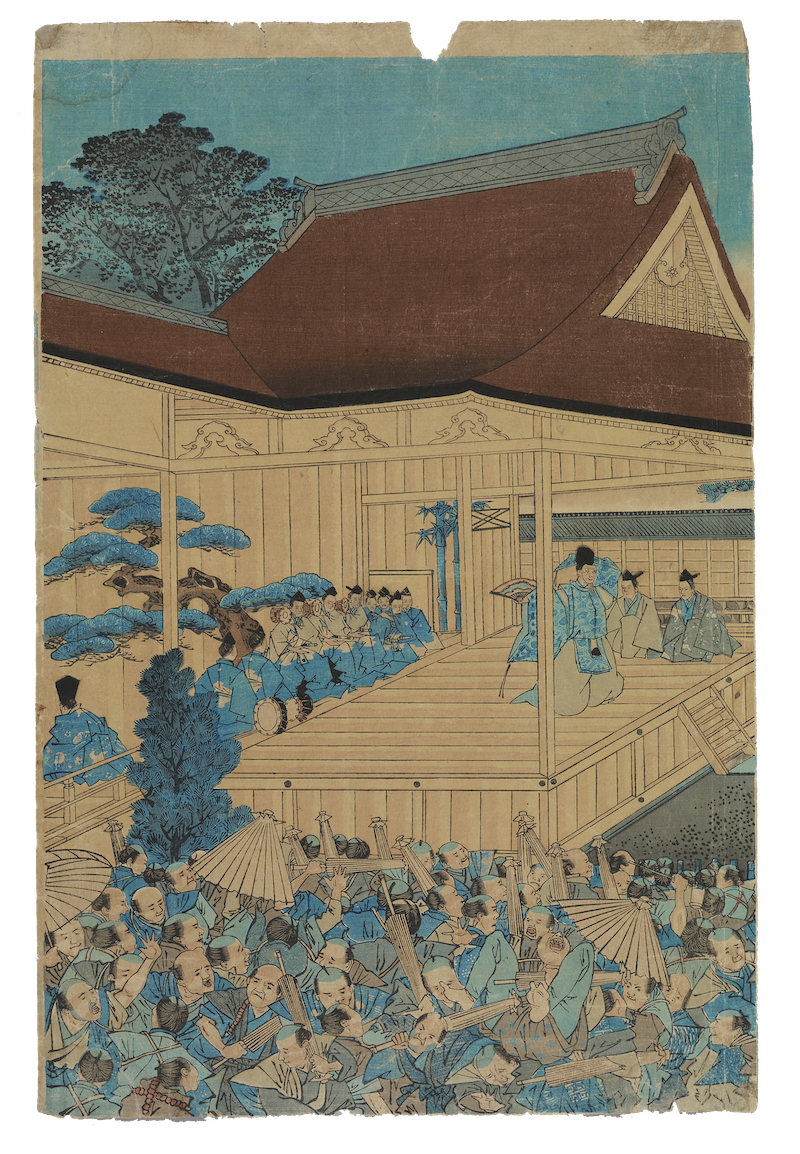

Kabuki was at the heart of the flourishing Japanese theater in the Edo period. Audiences loved the elegant costumes, make-up, spectacular backdrop scene paintings, and sets. However, it was the actors’ stunningly detailed performances and stage techniques such as mawari-butai (the revolving stage developed in the mid-1700s), seri (the rising and lowering of sections of the stage used since the mid-1700s), and hayagawari (lightening-fast costume changes) which drove audiences mad with excitement.

Amazingly, these spectacles are still seen today, which contributes to the incredible popularity of Kabuki. In fact, today’s classic plays were written predominantly during the Edo period. They were considered new works back then, but they were continually performed over the years. Consequently, they became the classics that are revered now.

The actors and their stage in the Edo theater scene

Actors during the Edo period were extremely popular with commoners, so much so that ukiyo-e woodblock prints of them became sought after Edo souvenirs. As a result, many scripts for Kabuki were written with a particular actor in mind. Also, famous Kabuki actors were paid very well.

With the incredible popularity of Kabuki and its actors, tickets could be expensive. The reason was because the audience could watch one play for an entire day while enjoying o-bento (lunch boxes) available between intermissions. In general, kabuki today is most similar to the kind of theater performed in the mid to the late Edo period.

In those days, theaters existed in every city in Japan. The largest ones stood in Edo and Osaka. In rural areas, amateur actors and farmers set up playhouses in small towns to perform noson kabuki (rural Kabuki). Sometimes, even the townsmen would call professionals to perform in their shrines and temples.

The lasting impression of the Edo theater scene

Kabuki had spread enormously throughout Japan during the Edo period. Bunraku plays were also loved by the Edo commoners. The narrative recitation style gidayu-bushi, a kind of song-like storytelling, was delivered by the tayu narrator. In addition, the shamisen player and the ningyo tsukai puppeteer also accompany the performances.

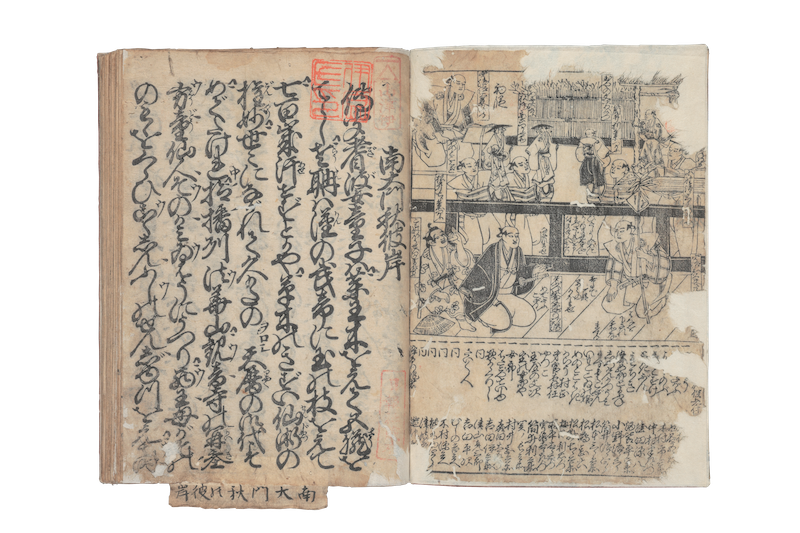

Fortunately, the masterpieces of acclaimed dramatist Chikamatsu Monzaemon (1653-1724) are still performed today. Unlike Kabuki scripts, Bunraku scripts were published. They were incredibly popular and widely read. The stories of Bunraku became so well-known among the people that Professor Kodama claims, “It may be no exaggeration to say that Japanese full-length plays were born from Bunraku…”

0

0