The Japanese Islands That Matthew Perry Helped Build

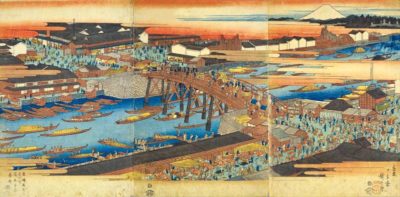

In 1852, America’s 13th president, Millard Fillmore, ordered Commodore Matthew C. Perry to sail to Japan and open its ports for trade. At the time, Japan was well over 200 years into its sakoku policy of isolation, which, among other things, barred Westerners from trading in Japan except for one port in modern-day Nagasaki. Perry was tasked with changing that, by force if necessary. To that end, he brought four warships to Edo Bay in 1853, rushing straight towards Japan’s capital with his cannons fully loaded, an act that quickly got the government’s attention.

Not being in any position to refuse, Japan allowed Perry to land in what is today Yokosuka, where he presented the government representatives with letters from the American president “asking” to open trade relations between the U.S. and Japan. Perry then said that he would return in one year, giving the government time to consider his offer. But this time, Japan thought, they would be ready for him.

The same year that Perry arrived in Edo Bay, one Egawataro Zaemon, also known as Hidetatsu Egawa, proposed defending Japan with the creation of batteries in the inland sea off the coast of Shinagawa. These artificial islands would be outfitted with cannons that would hopefully prove to be a match for America’s firepower. The name for the cannon fortresses at the time was “daiba,” which soon also came to describe the islands themselves. Construction of the daiba began as soon as Commodore Perry left Japan for Hong Kong.

Construction of the man-made Odaiba Islands begins

It was an incredibly ambitious engineering project. To create the artificial islands, large amounts of earth were transported from three sites to the coast of Shinagawa, which were then supplemented with soil drudged from the Sumida River. Next, nearly 5,000 trees were cut down in modern-day Chiba and carried by boat to Edo. Finally, about 1,000 stonemasons were hired to produce the stones necessary for construction of the daiba, to which people soon started adding the honorific “o” prefix, calling it “Odaiba.”

The original plan called for the construction of 11 batteries in Edo Bay, but due to financial difficulties only five ended up being completed. Construction on two more began but was halted, with plans for the rest being canceled indefinitely. Would it have been enough to defeat Commodore Perry and his warships? Doubtful, but Japan never had to find that out the hard way, because before the construction of the turret fortresses finished, the government decided not to risk it and ended its policy of isolationism. Thanks to an accord signed between the United States and the ruling Tokugawa shogunate, the ports of Shimoda and Hakodate were opened to American ships, finally bringing sakoku to an end.

As for Odaiba, the islands never got to be used for their intended purpose, which probably came as somewhat of a relief to the 5,000 soldiers chosen to man them. For the next 100 years or so, the area off Shinagawa continued to serve as a major port for the transportation of goods around Japan and produce seaweed, which it is known for even today. Between 1854 and 1965, all but two of the artificial islands were removed to free up shipping lanes, with the surviving ones becoming repurposed. Among other things, they have served as shipyards and housed war orphans following WWII.

The Rebirth of Odaiba

For decades, though, the islands and the surrounding waterfront area were mostly forgotten. Then during the mid-1990s everything changed. In order to help with Tokyo’s expanding population and ease traffic congestion, a plan was put in place to redevelop the capital’s unutilized areas into new, bustling city centers. With the construction of the famous Rainbow Bridge in 1993, which connected the Shibaura Pier and the Odaiba waterfront, all eyes fell upon the land surrounding the old turret fortresses.

In 1995, a plan was enacted to turn the Odaiba area into the city of the future housing over 100,000 people, luxury hotels, and businesses from all over the world. More than 1 trillion yen has been put into the project, which is why it’s so unfortunate that it didn’t really work out. But near the end of the 20th century, Odaiba started to find its own new identity. Instead of becoming the new worldwide center for business like Shinjuku, the area attracted shopping malls, convention centers, and even motorsports events.

It also became known as one of only two places that have direct access to Tokyo Bay waters, unobstructed by commercial or industrial developments. (The other one is Minato Mirai 21 in Yokohama.)

Odaiba Today

Today, Odaiba’s attractions include, for example, the now iconic Daikanransha Ferris wheel. Standing at 115 meters (377 feet) tall, it was the tallest Ferris wheel in the world upon its completion in 1999, and now stands as one of the many unofficial symbols of Odaiba, as does the Miraikan, a futuristic museum dedicated to emerging sciences and innovation. But Odaiba hasn’t forgotten about its roots. For example, Daibakoen is a popular park built on the third daiba battery where you can relax, camp out, and even admire the remains of the old fortifications.

Otherwise, Odaiba just so happens to also house a scale, 40-foot-tall replica of the Statue of Liberty. Originally erected as a tribute to the relations between Japan and France, the Odaiba version of the monument, now indelibly linked to America, overlooks Tokyo Bay and Rainbow Bridge, almost as if to make sure no one forgets the roundabout way in which the United States helped bring the whole area to life.

If you enjoyed this article, you might also enjoy:

Tokyo Bayside Story: Toyosu and Odaiba

Tokyo Trick Art Museum

The History of Yokohama: Perry, Ports, and Progress

Tokyo Bayside Story: Kita-Shinagawa and Tennozu Isle

0

0