Of the top four culinary superstars which emerged during Japan’s Edo period, soba was the first to grace the table. Soba is actually the Japanese word for buckwheat, the main ingredient of the popular noodle. Though buckwheat grain was introduced into the Japanese diet as early as the Muromachi era (1336 – 1573) in porridge form, soba-kiri (buckwheat noodles) did not start filling mouths until the Edo period. Soba-kiri’s influence was so potent that many traditions revolving around the noodles are still practiced today. Of course, that includes the New Year’s Eve special Toshikoshi soba.

Another carry-over from the era when soba ruled the restaurant scene is the blusterous slurping of noodles by the typically quiet Japanese people. In fact, slurping is the best way to savor the flavor of the traditional Japanese meal. So, there’s no need to shy away from noisily sucking them down.

Soba can be prepared and served in a variety of ways like Ni-hachi soba, for example. Ni-hachi soba uses a mixture of about 20 percent wheat and 80 percent buckwheat. Interestingly, the percentages correlate with its name — Ni (two) Hachi (eight). Also, the versatile noodles may be cold for zaru-soba or hot for kake-soba to warm hungry bellies. However you choose to enjoy Japanese soba, the energizing flavor never fails to disappoint.

Slurping Soba Day and Night

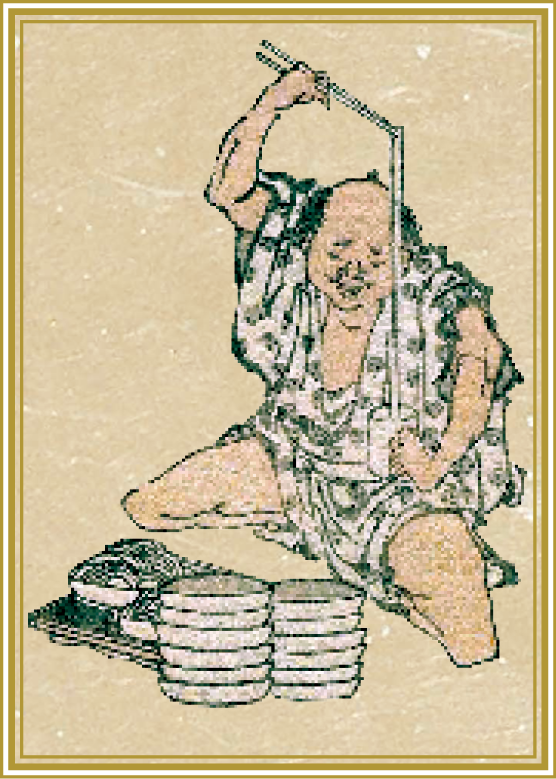

Along the busy streets in the Edo period, patrons were enticed by the call of shop owners and the hearty sound of delicious soba noodles being hastily slurped up by happy customers. The dish was such a hit among the Edo people that just about every neighborhood had at least one or two packed soba restaurants.

Along the busy streets in the Edo period, patrons were enticed by the call of shop owners and the hearty sound of delicious soba noodles being hastily slurped up by happy customers. The dish was such a hit among the Edo people that just about every neighborhood had at least one or two packed soba restaurants.

Because it was so cheap and convenient, soba-kiri became the first “fast food” in the growing gourmet city. However, after these eateries would close around 10 pm each day, there was no way to satisfy the craving for soba late at night. To meet the demand for tasty midnight meals, the mobile soba stall, or Yotaka-soba, business began to make the rounds in the evening. It wasn’t long until these foot powered noodle stalls took over the streets.

As the people of Edo devoured Soba day and night, their hunger for the delicious fast food grew and grew. So, soba restaurants were constantly evolving to keep the customers coming in for more. Competition became fierce, so local soba shops needed to differentiate themselves from other vendors. As a result, shops began using their own special flour, sauces, and cooking techniques.

The top three traditional factions of soba restaurants are Yabu with its strong dipping sauce and greenish colored noodles, Sunaba with a milder taste, and Sarashina which boasts a white color. What gives Sarashina-soba its whitish color is the removal of the dark buckwheat hull. Though these noodles have a more delicate sweetness, they lack some of the protein from the hull in the other two types. Each have their own recipes and styles which have lasted through generations. Today, these names still appear in many modern restaurants so customers can easily find their favorite style of soba among the densely clustered establishments.

Soba and The Flavor of Edo

Besides buckwheat, the main ingredients that make up a typical soba meal are the soy-based dipping sauce (soba-tsuyu) and the condiments (yakumi). These factors are what really give each dish its own identity and flavor. What set Edo-style soba apart was the extra strong soy sauce, koikuchi-shoyu. In fact, now it is the most widely used soy sauce around the nation.

The production of this sauce was a departure from the Kansai region’s subtler flavored Usukuchu-shoyu which was fermented less strongly. It also helped develop the distinct taste of soba-tsuyu in Edo. Yakumi, like chopped green onions and other condiments, also played an important part in the popularization of soba according to some theories — especially grated radish and later fresh wasabi which added even more of a kick to the powerful flavor of this classic cuisine. The strong flavor of soba provided a much-needed boost to tired workers who mostly did physical labor. In fact, it was likely a major factor in soba’s meteoric rise in popularity.

Where to slurp down great tasting soba: Kanda Yabu-soba

As it celebrates its 140th anniversary next year, Kanda Yabu-soba continues to serve high-quality buckwheat noodles to hard workers in downtown Tokyo, just as it did with the local craftsmen and laborers. It was their patronage brought the legendary soba restaurant such great success since 1880 when it inherited the original “Yabu-soba”, an established noodle restaurant. It was originally a samurai residence in Dangozaka before it was converted to a popular noodle-slinging establishment. Starting out simply as fast-food, now it boasts an expansive menu including the popular tempura-soba and kamonanban-soba. No matter what you choose or how you eat soba, the most important aspect is enjoying a wonderful meal with the people around you, according to the owner and 4th lead chef, Yasuhiko Hotta. Experience the classic, powerful soba flavor and the aesthetic of Edo Japan at Kanda Yabu-soba.

Kanda Yabu-soba

Address: 2-10, Kanda Awaji-cho, Chiyoda-ku, Tokyo

Hours: 11:30am – 8:00pm

URL: https://www.norenkai.net/en/portfolio-item/kanda-yabu-soba/

0

0