The Humble Origins of Shinjuku

Tokyo’s Shinjuku is like no other place in the world, although many like to compare it to Las Vegas. On the surface, it’s easy to see why some people would make that comparison.

Although Shinjuku isn’t a city in its own right, but rather one of 23 municipalities that make up the most populous parts of Japan’s capital, it does enjoy the status of a city. Specifically, a city that lights up the sky every night with its colorful billboards advertising everything from game centers and family restaurants to seedy cruising grounds in Shinjuku’s infamous Kabukicho red-light district. It all happens under the watchful eye of Godzilla, Shinjuku’s official tourism ambassador, whose statue towers over the area Gracery Shinjuku. All in all, it sure does sound like Nevada’s pop-culture-themed Sin City.

But in reality, the Las Vegas comparison is superficial at best. When you take a closer look at Shinjuku and its history, it becomes clear that it should actually be famous for its resilience. For centuries now, Shinjuku has been attacked, shut down, and even bombed, but it always got up to adapt and reinvented itself, emerging from the ashes stronger than ever. That is the true legacy of Shinjuku, and it started hundreds of years ago.

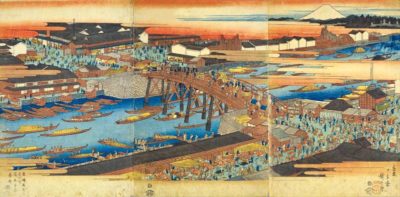

“Naito Shinjuku at” Yotsuya 1857

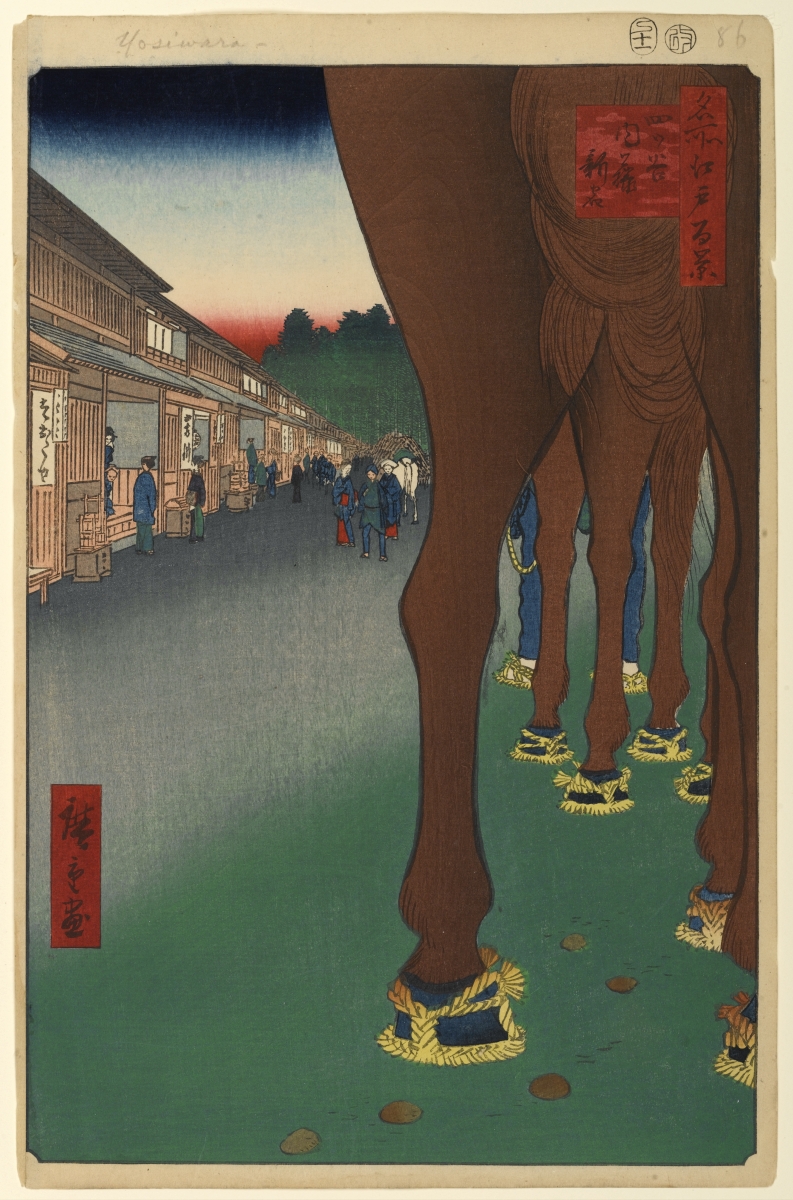

Let’s back up a little. Around the 16th century, people traveling to especially faraway places would use the “kaido”, a system of highways that crossed the country, connecting important city centers and government holdings. And just like with modern highways, the system was supported by a number of “pit-stop” inn-towns along the way, i.e. inn-towns known as shukubamachi that provided lodging, drinks, and entertainment to travelers. One such inn-town was eventually created by the government from confiscated lands belonging to the Naito clan, hence its name: Naito Shinjuku (“Naito’s New Inn/Lodgings”)

Rising from the Ashes

Shinjuku continued to grow, but until the 1920s, the area could only boast a water purification plant and little else, infrastructure wise. Then in 1923 the Great Kanto Earthquake happened, resulting in more than 140,000 deaths and so much damage to Tokyo that the Japanese government actually considered moving the capital to another city. But Japan persevered and soon started to rebuild. That’s when the country’s eyes fell on Shinjuku, which suffered only minor damages in the quake.

The area was quickly designated as a new “sub center” of Tokyo, and in no time became a symbol of post-quake revitalization. New businesses and people started to flock to Shinjuku (especially the western part), including one of the most famous Japanese department stores, Isetan, which moved its headquarters there in 1933.

The sudden rise in Shinjuku’s population also created the need to expand the local train station, first established in 1885. Originally just a stop on the Akabane-Shinagawa Line (today part of the Yamanote loop), Shinjuku Station expanded to accommodate three new major train lines around 1923.

It still wasn’t the convoluted maze that at times seems impossible to escape, like today’s Shinjuku Station, but it definitely marked the beginning of the area’s complete rebirth.

And then World War II happened.

With the bombing of Tokyo, huge portions of Japan’s capital were destroyed. Some estimates claim that by the end of the war over 85% of Shinjuku and the buildings in the surrounding area were gone. But again, Shinjuku survived. In the 1960s, it became the symbol for post-war redevelopment, having been chosen as the site for the capital’s new decentralized business hub, eventually becoming the Shinjuku that we know today.

The Complex Puzzle of Modern Shinjuku

Nowadays, 11 out of Japan’s 40 tallest skyscrapers are located in West Shinjuku, one of the busiest business districts in the world. Over the years, the distinct skyline has come to represent not just the area but also all of Tokyo and, in a broader sense, everything that is modern about Japan.

Then there are the ward’s art centers, theaters, world class restaurants and more. All of which stand in direct contrast to Shinjuku’s more lowbrow history of prostitutes, alcohol, and other vices. That ’s because Shinjuku has been built on the foundation of contradictions. It was a strategically and politically important inn-town, which also became famous thanks to prostitution and horse manure. It was the place of Japan’s postwar economic rebirth, and features to this day, one of the biggest concentration of seedy bars in the country. It’s also home to the Tokyo Metropolitan Government Building, and just a stone’s throw away is another of Shinjuku’s landmarks known as the “Omoide Yokocho”, which means “Memory Lane”

In short, it’s a place that mixes modernity with tradition, and the highbrow with the mundane and common. All of this remains in constant flux, changing and giving way to the other, but never losing that distinct Shinjuku feel. At least, that’s how things are now. How will they look in a few years? Nobody knows, but it will probably always feel like Shinjuku, because that’s what this unique technically-not-a-city city does. It goes through these constant cycles of rebirth while always remaining true to its complicated, convoluted, and contradictory history.

So be sure to give it a visit, if you ever get the chance.

Provided you can find your way out of Shinjuku Station.

By Cezary Jan Strusiewicz

Want to explore Shinjuku? Don’t feel lost, we have perfect walking routes for you.

Another 3hr trip – Shinjuku & Iidabashi and Another 3hr trip – Shinjuku

0

0