While we do not always give much thought to the special occasions we celebrate every year, holidays around the world are steeped in the rich cultural history of the regions in which they are celebrated. Many western holidays, for instance, come from the Judeo-Christian adaptations of pagan holidays that were celebrated deep in European history. Many eastern countries, on the other hand, are deeply influenced by religions such as Buddhism and Hinduism, and as such celebrate very different holidays and special occasions than Europeans and North Americans. Japan has a unique take on religion and national holidays. The country’s culture is not only steeped in a rich Buddhist history, but is also informed by certain remnant practices of the Shinto religion, the original religion of the country’s ancient people. And yet, as an eastern country with very close connections to western countries like the United States, certain holidays also reflect these western influences. As such, Japanese public holidays blend Eastern and Western traditions in unexpected ways.

Japanese Public Holidays in Summer

O-bon:

The origins of o-bon festival are attributed to the holiday’s Buddhist roots. Some stories say that one of Buddha’s disciples learned that his mother was suffering in the afterlife. Upon discovering this, he asked Buddha how he might help his mother and ease her suffering. Buddha told him to prepare offerings for Buddhist monks that would soon be returning from their summer travels. The disciple followed Buddha’s instructions, and his mother was freed from her suffering.

The official dates of o-bon are usually 13 August to 15 August (or 13 July to 15 July,, depending on the region), although there are often festivities stretching beyond these dates.

Traditions and Festivities:

The main o-bon traditions are focused upon the brief return of one’s ancestors from the afterlife. Most Japanese will return to their hometowns to clean the graves of their ancestors and welcome them home. Upon the first evening, families light lanterns to guide the deceased back to the land of the living. The lanterns are hung in front of each family’s home and offerings to the ancestors are set out at a small altar within the house. On the last day of the festival, the lanterns are set afloat upon the nearest body of water, guiding the spirits back to the afterlife.

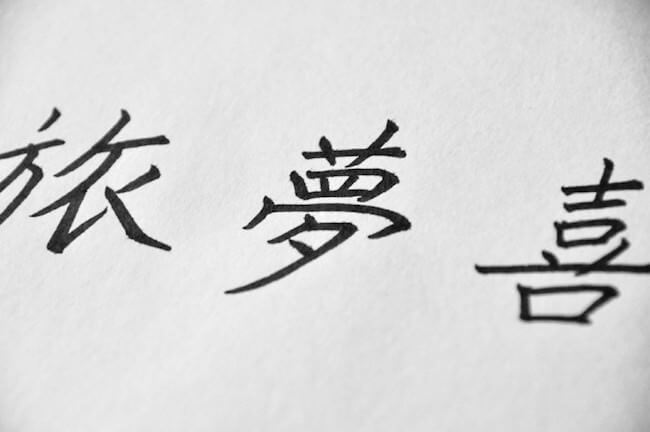

Publicly, o-bon is accompanied by a variety of festivities that vary region by region. Kyoto, for instance, is famous for its Fire Festival, during which the Japanese character 大 (meaning big or great) is set into a hillside and lit aflame. Most regional festivals are also accompanied by their specific take on the bon-odori – a special dance that is performed at the beginning of o-bon to welcome the spirits back from the land of the dead.

Food:

As an occasion that is celebrated with great public festivities, o-bon is usually accompanied by stand after stand of Japanese street food. This includes dishes like takoyaki (pan-fried octopus balls), yakisoba (stir-fried Japanese noodles with vegetables and beef or chicken), dango (Japanese rice cake balls that are skewered and served with some kind of sweet topping), and kaki-goori (shaved ice that is served with a variety of toppings). Within the home, families may also celebrate with foods like chirashi-zushi (deconstructed sushi in which the sushi rice is served in a bowl and topped with various sushi toppings) and maki-sushi (sushi that is rolled into a cone shape with the seaweed and rice on the outside and the other ingredients stuffed into the center).

Where to celebrate Japanese public holidays in summer:

O-bon is celebrated all over Japan, although the most famous festivals are held in Kyoto, Nagasaki, Tokushima (Shikoku), and Mikasa (Hokkaido). Each festival has its unique flavor, accompanied by region-specific fun and food.

Japanese Public Holidays in Winter

O-shougatsu:

The most important of Japanese holidays, o-shougatsu celebrates the coming of the new year. As in many Asian countries, the festivities were originally held in accordance with the Chinese lunar calendar. However, during the westernization of Japan through the Meiji era, the dates were changed to coincide with western New Year’s traditions. Despite the changing of the dates, however, the practices that accompany o-shougatsu are still very much in accordance with the Buddhist traditions from which the holiday was born, 31 December to 3 January.

Traditions and Festivities:

Although many people will take December 30th to travel back to their hometowns for this Japanese public holiday, the 31st is when the New Year’s traditions really begin. Some people spend the evening in the more western style of parties and countdown. However, many families will simply spend a quiet evening in, watching television, eating soba, and awaiting the new year. Within the first few days of the new year, families will gather to give o-toshidama, or gift money, to the younger generations and visit local temples and shrines to pay their respects and pray for good fortune in the coming year. The first prayer of the year at temples and shrines is a practice known in Japanese as hatsumode. It is also a common practice to send new year’s greeting cards to one’s friends, extended family, and colleagues.

Food:

In the past – and even now in many rural areas -, the vast majority of stores and markets are closed during o-shougatsu. As a result, families often spend quite a bit of time preparing a number of dishes to last through the holiday until stores reopen. Along with the festivities, the traditional foods also begin on New Year’s Eve with toshikoshi soba, Japanese buckwheat noodles. This meal is supposed to bring longevity and good fortune. However, if you partake after midnight, it is said that you will call bad luck upon yourself. During the first days of the new year, families share meals of o-sechi ryouri, a dish that includes a variety of components such as fish, beans, and vegetables, most of which are preserved to last for several days. For the first day of the new year, in particular, many people enjoy a special soup called o-zoni that is made with mochi (rice cakes) and vegetables, along with other ingredients.

Where to celebrate Japanese public holidays in winter:

While many places still tend to shut down during o-shougatsu, big cities such as Tokyo and Osaka are seeing more western-style festivities, complete with New Year’s Eve festivities such as concerts, performances, and the new year countdown.

Honorable Mention: Christmas

Unlike Western countries, Christmas is not a national holiday in Japan. It is, however, widely celebrated as an occasion for decorations, parties, and dates. Surprisingly, the feature dishes during Christmas include Kentucky Fried Chicken and pizza.

Japanese Public Holidays in Spring

Japanese Public Holidays in Golden Week:

Golden Week is the most popular time of year for leisure traveling. Contrary to assumption, Golden Week is not a one long, consecutive holiday. In reality, Golden Week is a combination of one-day Japanese public holidays stacked upon one another.. The holiday starts with Showa Day(29 April ) and spans Constitution Memorial Day(3 May) , Greenery Day(4 May) and Children’s Day(5 May), usually with a weekend somewhere in between.

Traditions and Festivities, and Foods:

There is no one way to spend Golden Week for Japanese. As the other significant holidays are typically dedicated to traveling back to one’s hometown, Golden Week is often the time during which people visit other towns and countries. Any number of different cultural festivals can be found during this time, complete with any number of foods to match.

Johanna Collier

Johanna Collier is an American writer based in Tokyo. In addition to writing for Japan-based travel and gaming industries, she is active in the Japanese entertainment industry, regularly training in action, stunts, dance, and other performance arts. She is also an avid and adventurous foodie and culture lover and is always on the lookout for a new adventure.

*Disclaimer:

This article was written by an outside writer, and WAttention is not responsible for any damage caused by the information on this page. Please be aware that the accuracy of the information posted in this article is not guarantied, and the content may be changed without notice.

0

0