Hot nights, traditional costumes, portable shrines and the rhythmical beating of drums immediately spell out matsuri, summer festivals, to any Japanese person. One of the three biggest in Tokyo and one of the earliest, always in the third weekend of May, is the Sanja matsuri in Asakusa. For three days in a row, it celebrates three people with three main mikoshi, or portable shrines, in Sanja shrine. The locals also have their own holy mikoshis that they carry around the streets, each neighborhood association, or chokai,

having one.

We took part in the preparations and activities of the “Nishiasa Sankita (Nishiasakusa Sanchome Kita Chokai)”, a neighborhood association that has the biggest mikoshi among the locals. Mere coincidence, but even the name of this association features the number three or ‘san’ in Japanese. With Sanja festival it seems it is all about the number three.

Friday morning preparations for the Sanja festival

I felt privileged from the start, while glimpsing the careful uncovering and assemblage of the portable shrine of Nishiasakusa Sanchome Neighborhood Association. Stopping in their tracks in the scorching May sun, locals were taking photos of the rare moment I was invited to witness. “It’s maybe the biggest mikoshi in Sanja matsuri,” one of the Nishiasa Sankita members proudly says to me. This mikoshi with carved wooden dragons and topped with a golden phoenix has been handmade by one of the rare mikoshi artisans in Tokyo. The people assembling it tell me that later a talisman will be fetched from Sanja shrine that will put part of God’s soul inside the mikoshi. Handymen that do this assemblage carefully tighten the ropes under the gaze of the kashira, a person historically in charge of city safety. Abe-san, the kashira for Nishiasa Sankita has been doing this forever. Everyone respects him and the other community elders.

In the nearby garage traditional music and lanterns heat up the matsuri atmosphere. The locals come to help out or donate to the association. The event president, Kazuya Nakajou, says that this is his favorite thing – everyone working together. “It’s not hard because everyone helps me,” he is humble when I ask him how hard it is to organize an event like this. He explains that one of the purposes of the portable shrines being carried through the streets is showing people God is protecting them.

Carrying the Nishiasa Sankita mikoshi

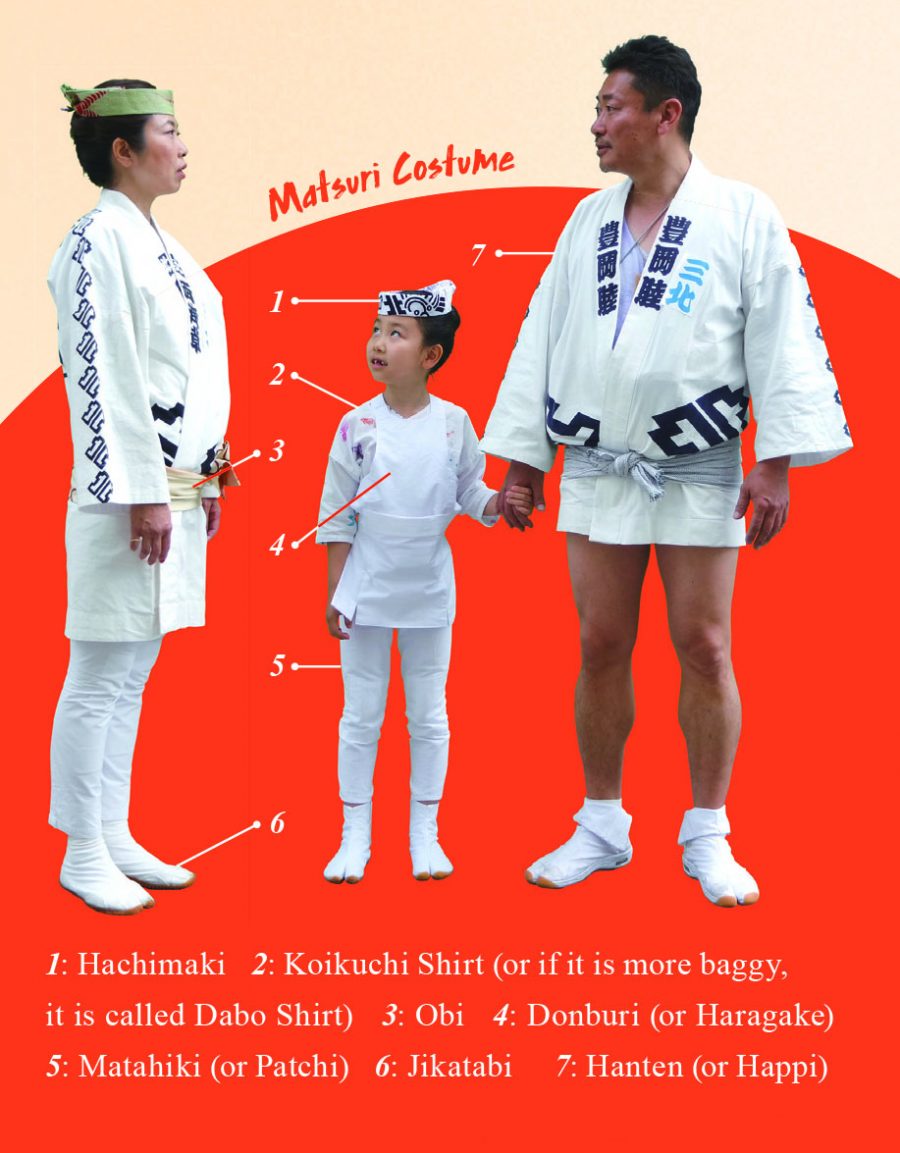

The excitement the next day is almost palpable. The Nishiasa Sankita locals mostly wear white hanten coats with black letters and I am given one too. Grandparents, children, pets – we are all united under one symbol. The drummers playing the matsuri music known as kagura solemnly lead the way. The gold of the mikoshi is ablaze in the golden May afternoon. People who carry the mikoshi have the most unusual maps of emotions on their faces – both strain and joy. The people around them encourage them and occasionally switch place with them to share the load. It is then when I am pulled in, as many others are, to carry the mikoshi. I am wearing the hanten and I decide to accept. Shouting “Oisa, oisa!” as everyone else is, seems to magically help!

Kagura is also the word for the music itself at matsuri.

In the breaks between the mikoshi carrying everyone seems to be having a great time. They share drinks and meals and exchange witty banter. The Saturday Sanja matsuri activities of Nishiasa Sankita are concluded by one last carrying of the mikoshi and this one is ladies only. Of course, I was pulled in again to carry it!

It seems Sanja matsuri is all about the number ‘three’. Michael Feather ended up documenting the festival for three consecutive years and I ended up carrying the mikoshi three times in the same day. Neither of us had that planned, but Sanja matsuri has a way of lifting up your spirits and giving you a push into new experiences.

Check Interview with Michael Feather – Capturing Precious Moments from Sanja Matsuri to read about Michael Feather’s experience of Sanja matsuri.

Mingling with the Locals and Properly Matsuri-ing

Sitting down to share food and drinks with the locals, I finally felt what matsuri festivals mean to Tokyoites today – being together, here and now as it has always been . Smiling and sharing moments with people from all ages and in our case, people from all corners of the world. The spirit of summer festivals and portable shrines is to show everyone that they are one community. I felt that the spirit of the matsuri nowadays is showing me too that I can belong in a place where families live for generations but they open their arms and hearts to anyone else in a matsuri-mood.

Read more about the The Roots and History of Summer Festivals in Japan.

MATSURI COSTUME

0

0