Japanese tea is popular around the globe for its flavor and health benefits. With a place on the table along with many traditional dishes, it rises to the top of the country’s culinary culture. However, this special drink is more than just a thirst quencher. Japanese tea — like matcha (powdered green tea), hojicha (roasted green tea), and green tea — plays a major role in the spirituality of Japanese culture, especially during the tea ceremony, or sado. Even Tokyo, a shining example of modern Japan, finds quiet time for this centuries-old tradition, with innovative twists. There are many places to experience Tokyo tea culture.

Sharing Tea with Kobori Sojitsu:

A Grand Master of Enshu SADO School

The art and Philosophy of the tea ceremony have influenced many aspects of Japan’s aesthetic and spirituality throughout the years. The ritual, with its choreographed motions and various utensils, was considered to be a highly refined cultural experience. Even some of Japan’s most fearsome warriors thought so. Like a delicious Japanese dish, though the main ingredients are similar, the presentation of the tea ceremony differs across Japan. The reason is because masters have their own interpretations of the art. Of course, that means that the Tokyo tea culture is unique.

Enshu SADO School is a tea ceremony pioneered by Kobori Enshu, a feudal lord in the early 17th century. This style incorporates the elegance and powerful presence of the Japanese samurai who enjoyed the refinement of the tea ceremony. After 440 years, Tokyo’s Enshu SADO School continues the ritual and philosophy. Obviously it contributes greatly to Tokyo tea culture today. The philosophy of Enshu SADO School runs deeply through all of the art presented during the tea ceremony. So even though the ritual is centuries old, new ideas and works are formed with Enshu SADO School as the backbone.

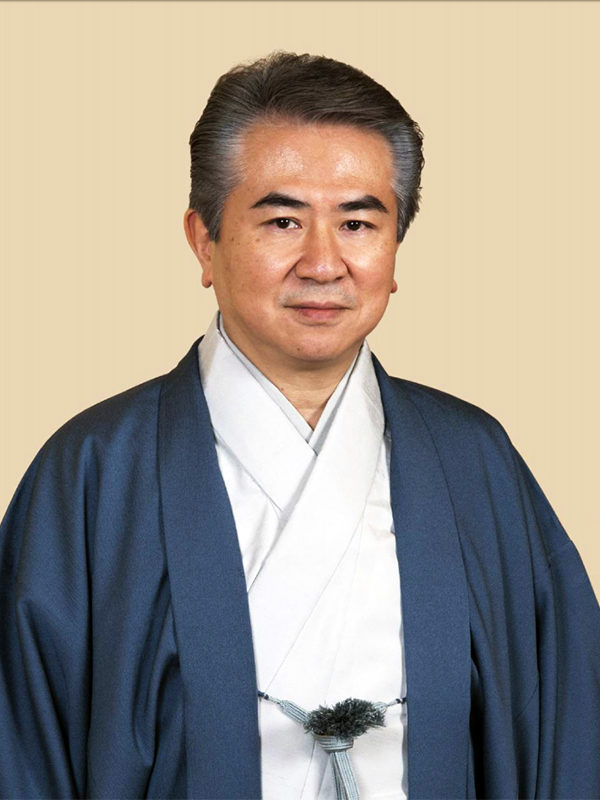

Kobori Sojitsu, the 13th Grand Master of the legendary school, keeps the traditions of the Japanese tea ceremony as the core of the school. Listening to him speak with elegance and confidence, the spirit of the Japanese samurai filled the room. On the walls were brilliant works of art striking balance between subtlety and drama — a feature of Enshu SADO School.

The leaders who influenced Kobori Enshu and Tokyo tea culture

As the 13th Grand Master of Enshu SADO School, Kobori Sojitsu knew the story of Kobori Enshu, the original Grand Master, as if he had lived the life himself. At the time of Kobori Enshu’s birth in 1579, it was nearing the end of the Sengoku period under the reign of Azai Nagamasa. By the time he was 10 years old, he was already gaining favor among Sengoku military commanders. They saw great potential in his many talents.

Enshu was able to establish connections with notable historical figures like the warlords of the Toyotomi family through serving tea. From then, he met Sen no Rikyu, who served tea to the legendary generals Oda Nobunaga and Toyotomi Hideyoshi, sparking Enshu’s interest in sado. When he was 15 years old, Enshu’s father introduced him to Furuta Oribe, who studied under Sen no Rikyu and also served Oda Nobunaga and Toyotomi Hideyoshi. Eventually, Enshu succeeded the legendary tea masters.

The end of an era and a cause for reflection

Though Enshu studied under the most influential tea masters of their time, he did not immediately start working as a tea master himself. Instead, he spent his time as a skilled administrator in the Edo Bakufu, the feudal military-style government during the Edo period (1603-1868). During that time, he grew close to feudal lords, great merchants, monks, and even the emperor of that time, Go-Mizunoo. As the Sengoku period (from the end of 15th century to the end of 16th century) faded deeper into the past, the Tokugawa Shogunate longed for peace and culture. Eventually, he became something like a chief of Cultural Affairs, where he could focus on refinement in the new age. At this time, Enshu’s ideas began to enter the mainstream.

Kirei-sabi: Integration of sophistication and simplicity Tokyo tea culture

Evolving from masters before him—Murata Shuko, Takeno Jouou, Sen no Rikyu, and Furuta Oribe—who added zen spirituality, poetry, simplicity, and art into the tea ceremony, Kobori Enshu used his fine taste to mold the concept of kirei-sabi. This is the core essence of Enshu SADO School which helped shape Tokyo tea culture.

Kire-sabi is where spirituality meets beauty and luminance. This quality of Enshu SADO School is senrensei no aru chowa no bi, which means “the beauty of harmony with sophistication.” Looking at the calligraphy, paintings, flower arrangements, and teacups, a calmness sweeps across the room. Unlike some other forms of art and fashion, kirei-sabi doesn’t try to overwhelm you. Instead, it elegantly focuses on a key aspect to maximize the impact of the subject. Kobori Sojitsu describes this balance like a good film with the main character in the spotlight who is supported by the other cast members. If one actor were to attempt to outperform the lead, the art would suffer as a whole. This sense of mutual respect and thoughtfulness — known as wakeiseijaku — forms the canvas on which sado art pieces are created.

That theme also translates into the tea ceremony itself. Enshu believed that one should not selfishly put themselves and their opinion first. It is a sentiment that can be felt while drinking and being served tea. It was an idea that came to Enshu during the new era of relative peace. In times of war, it was natural to put oneself first. That’s because it was never certain what fate would hold the next day. As the age became more harmonious, there was time to focus on others and show respect by putting them first.

From that aspect, it is easy to see how the ritual of the tea ceremony influences Japanese culture in daily life and Tokyo tea culture. Kobori Sojitsu is pleased to see its effects on young children as they try their first tea ceremony. Even the simple act of saying “osakini itadakimasu” (excuse me for going first), starts to make the children consider others. These humble acts plant the seeds of respect and courteousness that can help children grow into mature, sophisticated adults.

The philosophy of “Keiko-Shoukon,” present in the ceremony, is based on meditating upon antiquity and comparing the present with the past. Despite its long history, the Japanese tea ceremony Enshu SADO School focuses more on refinement than rustic materials and ways. With that spirit, Grand Masters like Kobori Sojitsu will continue to create beautiful works of art in the harmonious setting of the Japanese tea ceremony and Tokyo tea culture.

Kobori Sojitsu

The 13th Grand Master of Enshu SADO School

He received Fuden-an Sojitsu as his zen and tea name from the Grand Zen Monk Fukutomi Settei, the head of the Daitoku-ji Temple in Kyoto in 2000 after his study there. He became the 13th Grand Master of Enshu SADO School on New Year’s Day in 2001. As a part of keeping the traditions and spirituality of the tea ceremony, as well as creating a tea ceremony that continues to be meaningful in a contemporary world, he collaborates with artists in various fi elds and actively participates in overseas cultural programs. He believes that “tea brings richness in minds”.

*All the photos © Enshu SADO School

0

0