Tokyo 1964: A View of the City

In 1959, when Tokyo won its bid for the Tokyo 1964 Games, it was scarcely more than a glorified collection of shantytowns. At that time, the Japanese nation was still wrestling its way out of the wreckage of World War II. To turn the city into a high-tech megalopolis fit to host one of the world’s greatest sporting events in five short years was a civil engineering feat of unparalleled precedence. It may have come at a cost, but for a nation languishing on the fringes of international society, it marked an irreversible change in fortunes for Japan and its capital city.

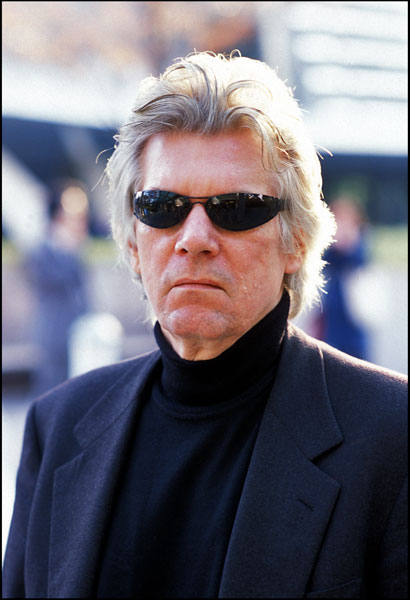

I spoke with Robert Whiting, a Tokyo resident during the Tokyo 1964 Games and author of Futatsu No Olympics: Tokyo 1964/2020 – an autobiographical treatise on Tokyo’s Olympic history, set to be published in English in January 2021 – who shared his thoughts on the effects of the Tokyo 1964 Games and the prospect of the Tokyo 2020 Games.

Whiting first arrived in Tokyo as a G.I. for the United States military in 1962. “The level of construction at that time was amazing,” he says. It was a time of rapid urban development and economic upheaval which saw a rush of workers flock to the city with pipe dreams of prosperity; it was the eastern land of milk and honey, and it caught Whiting hook, line, and sinker: “The energy level of the city just sucked me right in, I just couldn’t get enough of it”.

Building a World City

As the 1960s approached, Tokyo was lacking the necessary resources to host a global sporting showcase. In fact, it had only one five- star hotel (the aging Imperial Hotel), inadequate sewage and water filtration systems, hygiene and rat infestation problems, a lack of proper transport infrastructure, and a host of other logistical issues. Whiting tells me, “In 1959 when they were awarded the Tokyo Olympics, most people thought it was crazy to have an Olympics in Japan at that time,” though he’s quick to mention the “amazing” nature of the city’s redevelopment plans. “In a five-year period from 1959 to 1964 [the Tokyo Metropolitan Government] put up 10,000 new buildings, five five-star hotels, two new subway lines, they built a monorail from Haneda [Airport] into the city, and then they built the Shinkansen bullet train from Tokyo to Osaka. It completely transformed the city of Tokyo.” he says.

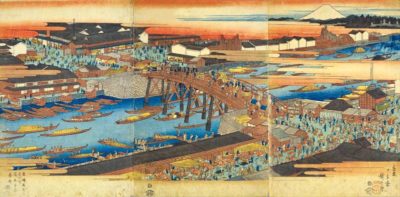

The changes, welcome as they were, did come at a cost. “There was a dark side,” Whiting observes. One of the most criticized visual scourges was the construction of a concrete highway directly over the historic Nihonbashi Bridge, which Whiting described as “´Zero Point´ in Tokyo.” The unsightly highway, erected a mere 10 feet above the bridge, permanently blocked the postcard-worthy view of Mount Fuji from the walkway (though plans have been made to move the highway underground as part of a Nihonbashi rejuvenation project). Marine life in the Kanda river didn’t fare much better. “[The construction] destroyed the river culture,” he says. Whiting also cites issues with soaring construction costs and bureaucratic corruption, yet he caveats said issues by pointing out: “Every Olympics makes mistakes… Historians have called this the greatest urban transformation in history. In that case, Tokyo was unique in the history of the Olympics.”

AkasakaMitsuke

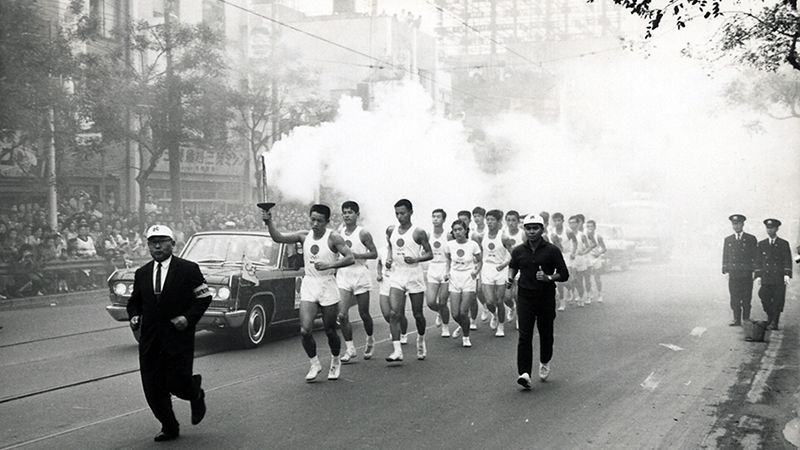

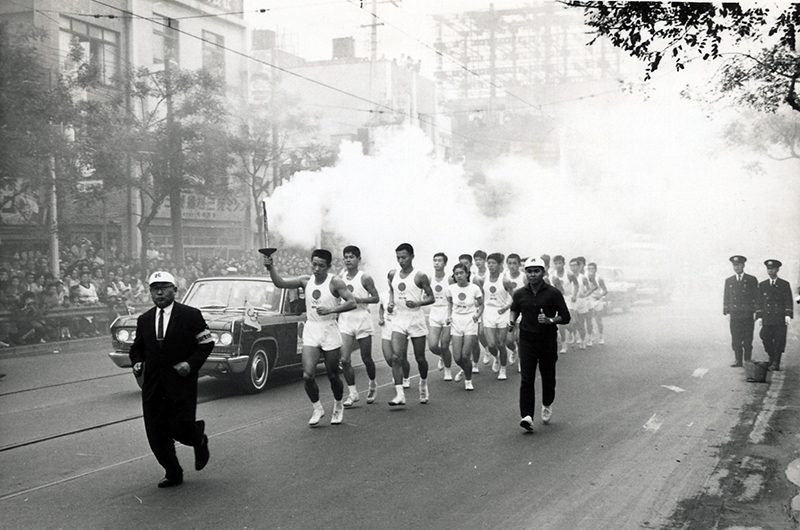

The Road to Greatness

Japan’s mounting struggles in the wake of the Second World War were still a part of the social zeitgeist in the lead up to the Games, so I asked Whiting about the sense of national pride among the Japanese populace in the early 1960s with the Games looming over the immediate horizon. “In the beginning, most Japanese people didn’t want the Olympics; they didn’t think Tokyo was ready,” he replied.

Yet by the time the opening ceremony rolled around, there was a seismic emotional shift among the natives. Pride had usurped dismay in the nation’s collective consciousness. Whiting watched the Games inaugural broadcast – the first ever Olympic opening ceremony to be broadcast live across the globe – with several Japanese acquaintances, and recalls them watching it “with tears in their eyes.” The landmark event represented Japan’s official re-entry into the global community.

In retrospect, the Tokyo 1964 Games was the catalyst that sent Japan off on the road to greatness. Whiting says, “It provided the infrastructure for global trade. Investors could come to Tokyo and stay in these comfortable hotels and collaborate in corporate headquarters. People felt that Tokyo was as advanced as any other city in the world – central Tokyo certainly was – and without the Olympics, it wouldn’t have happened.”

Looking Toward the Future: The Tokyo 2020 Games

The Tokyo 2020 Games is mere months away, and Whiting is relatively upbeat about the Games return to Japan. “The 2020 Olympics will show people a new side of Tokyo. Most people, when they think of Tokyo, probably think of Tokyo Tower, Asakusa, and Kannon Temple. They don’t know about Odaiba and this second city center that’s being created around Tokyo Bay,” he says. “It’s my belief that Tokyo is the greatest city in the world right now.” This statement carries a lot of stock coming from a man who has lived in cities as far-flung as New York, Paris, Geneva, Los Angeles, and Stockholm. To back it up, Whiting notes several quality of life statistics in which Tokyo is a consistent global front-runner: GDP, number of Fortune 500 headquarters, number of Michelin-starred restaurants, efficiency of the transport network, literacy rates, and levels of public safety.

And Whiting is not alone in his feelings toward 21st century Tokyo. By 2018, Tokyo had actually passed Paris as the world’s leading tourist destination. Trip Advisor, the internet’s largest travel website, asked its users to rank the 37 top cities in the world in terms of the ‘most satisfying’ to visit. Tokyo was voted number one, topping several of the 16 categories listed including: local friendliness, taxi services, cleanliness and public transportation.

One problem for the Tokyo 2020 Games, according to Whiting, however, is the time of year the event is set to take place. When Tokyo made its initial bid in September 2013, a spokesman for the Japanese Olympic Committee (JOC) suggested holding the Games between July 26 and August 11 as it was a ‘mild, sunny time of year and, therefore, conducive to outdoor sports.’ “[This] was a lie,” Whiting remarks. With temperatures usually well above 30 degrees Celsius in mid-summer, combined with stifling humidity, it’s hard to argue with. (It was recently announced, however, that several long-distance running and speed walking events would be moved to the milder climes of Hokkaido in the north; a degree of common sense has prevailed alas.)

Concerns notwithstanding, Whiting tells me, “I think one of the good things about this Olympics is that people will see what a modern technological marvel Tokyo is right now. If you stand on the Rainbow Bridge at sunset and look at the skyline of Tokyo now, it’s as impressive as any skyline in the world.” He also suspects this introduction of Tokyo to an even bigger global audience should have positive economic effects in the long run – despite the consistently rising costs of the Tokyo 2020 Games. He mentions the first Games to be broadcast on 8K television, a Maglev train demonstration, and the introduction of driverless cars and translating robots to the city as other technologically-advanced by-products of Tokyo hosting the Tokyo 2020 Games. They will go a long way in promoting what he has previously referred to as the “Japan Brand” – Japan presenting itself as a global front-runner in the realms of consumer and infrastructural technology.

Shinagawa Station

Race to the Finishing Line

Bureaucracy still stands as a roadblock to progress in coordinating the Games. This includes a deluge of conflicting organizations and ministries involved in the preparations who refuse to sing from the same hymn sheet. “I think what makes Tokyo interesting watching these Olympic preparations is that while Japan may be highly organized, when you look at the actual structure of the Olympic effort you see how disorganized it is,” says Whiting. “There are five groups that are supposedly controlling the Olympics… so you have all these groups who don’t know what each other is doing. Case in point, the head of the JOC replied to criticism of the Hadid National Stadium selected by the Japan Sports Agency and its subsequent cancellation by Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, by saying ‘Don’t blame me. I had nothing to do with it.'”

He recalls similar issues in the build-up to 1964, saying that people thought it was going to be a “colossal failure” just over a year out from the event. “But somehow, it all works in the end,” he adds. It’s on this brighter note that Whiting finishes, offering a beacon of hope for believers and naysayers alike: “I think they’ll do everything that’s humanly possible to get [the Olympics preparations] done in time, and I think it’ll be a great feather in Japan’s cap. Japan pulled off this Rugby World Cup – they did a great job – and they’ll do it again.”

Robert Whiting

Robert Whiting was born in New Jersey, raised in California, and first came to Japan with U.S. military intelligence in 1962. He is the author of several successful books on contemporary Japanese culture, including Tokyo Underworld, The Meaning of Ichiro, The Chrysanthemum and the Bat, and the best-selling You Gotta Have Wa (A Book of the Month Club selection, a Casey Award finalist, and a Pulitzer Prize candidate) and has served for the past four years on the Board of Directors at the Foreign Correspondents Club of Japan. The English version of his latest book Futatsu No Olympics, published by Kadokawa (photo below right), will be released in January 2021 in English as Tokyo Junkie by Stone Bridge press.

0

0