Covid-19 isn’t the first epidemic to strike Japan. In fact, the country has survived smallpox epidemics in 735 and 737, several cholera outbreaks throughout history and a massive cholera epidemic in the summer of 1858. There were also the global flu pandemics, such as Spanish flu, in the early 20th century.

The Daibutsu (Great Buddha) at Todaiji Temple and a pandemic

As the presence of the Daibutsu (Great Buddha) at the Todaiji Temple in Nara prefecture can attest, COVID-19 isn’t the first epidemic Japan has faced. Standing an impressive 15 meters tall, the Great Buddha is the largest of its kind in Japan. It was constructed with over 400 tons of bronze and donations from all over the country. These donations came from a special tax.

It was commissioned during the Nara period (710–784) in 745, and completed around 752. Its commission came on the heels – and, indeed, was prompted by – a turbulent time in the history of Japan. At that time, the country had suffered a major smallpox epidemic that lasted from 735-737. Sadly, the outbreak killed roughly one third of the whole population. In an effort to bring some peace to his country following not just the smallpox, but crop failures and the loss of his own infant son, Emperor Shomu commissioned the building of Todaiji Temple. Now the monument is a World Heritage site, and people still believe the Great Buddha protects Japan against any more infectious diseases.

This same hope can still be seen among Japanese people during this time of emergency. As evidence, for the first time in history, monks have performed televised (and live) Shinto rituals at the Todaiji Temple, along with a traditional Buddhist memorial service. The aim is to bring comfort to those people who remain indoors.

They are not the only place to air such ceremonies. Both Hieizan Enryakuji Temple (head of the Tendai sect) and Hiyoshi Taisha have broadcast traditional Buddhist rituals and a memorial service. The TV station also decided to broadcast live feed of the Great Buddha, in the hopes that the people at home will be able to find some solace in the image.

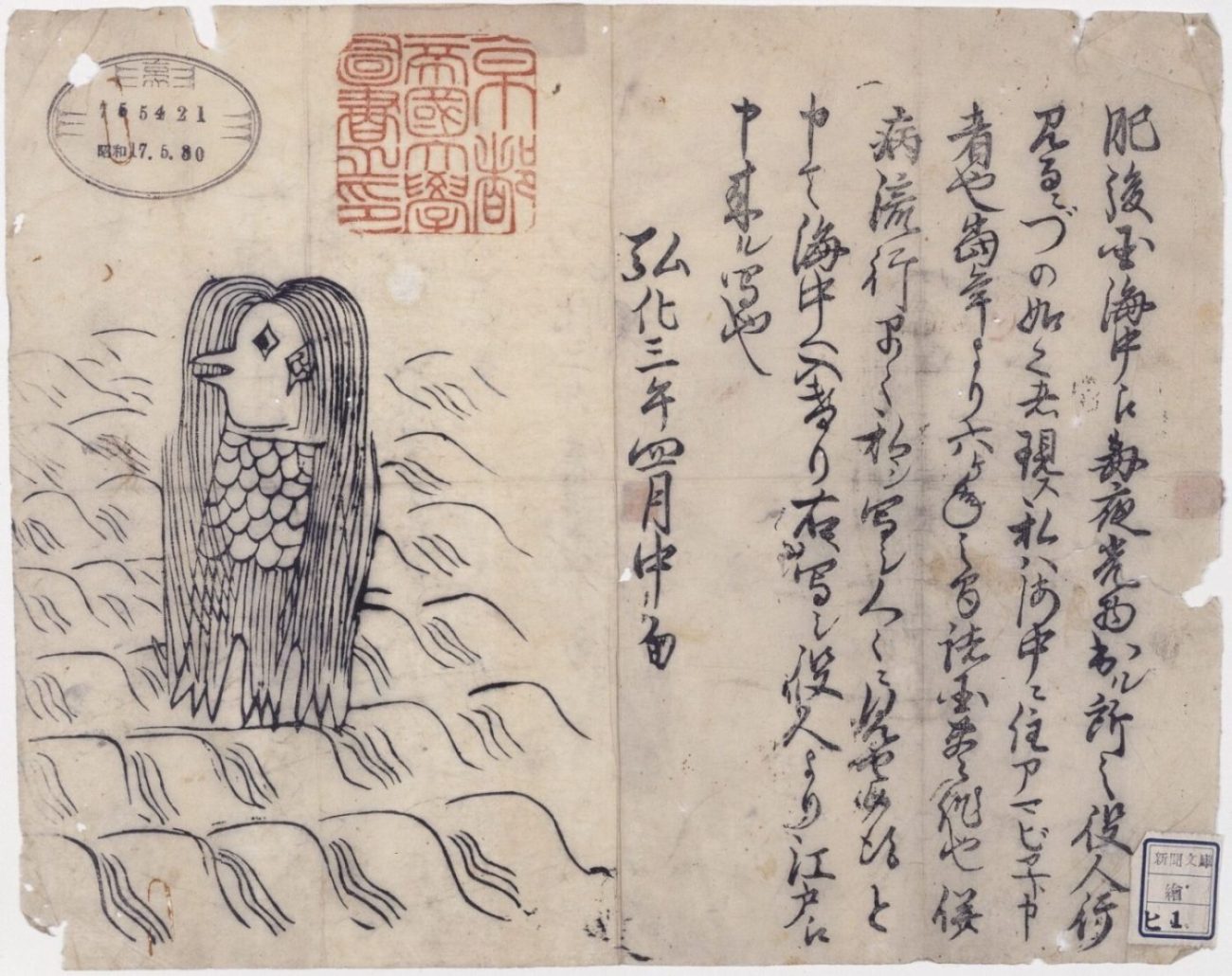

The monster amabie in hope of an early end to the pandemic on SNS

Japan has always had its fair share of yokai (supernatural entities). Some are more famous outside the country than others. Recently, a lesser-known yokai called an amabie is trending on social media. The yokai pops up under the hashtag #amabiechallenge in Japanese.

There is only one record of amabie in Japan’s history, and that’s in a news sheet from the Edo period (1603 – 1868). In it, the amabie appears as a three-legged yokai with long hair and a beak. Additionally, it is covered in scales from the neck down. Despite its unusual appearance, the amabie is benign. In its appearance back in the mid-19th century, it came to Higo no Kuni (modern-day Kumamoto prefecture in Kyushu), prophesying abundant harvests for the next six years. However it also brought a warning of an impending epidemic as well. The yokai then told the one who saw it to copy its picture and show it to others.

This last part has given rise to a sudden resurgence and influx of drawings, sculptures and even cosplays. In addition, drawing an amabie is said to protect people against sickness. With that in mind, people are posting pictures on SNS of amabies in all kinds of art styles, from cute chibis to beautiful, mermaid-like depictions. Also there are more serious renditions of this friendly yokai. One enterprising group is even attempting to build an underwater amabie robot to combat the coronavirus! In fact, the general public is not alone in this effort. The Japanese health ministry itself also featured the amabie in a tweet regarding COVID-19.

Japanese festivals and a pandemic

Japan is famous for its festivals, and most especially its hanabi-taikai (firework festivals). While there are nearly a thousand firework festivals up and down the country every year. Each has its own distinct flair, and one of the most famous is the Sumidagawa River Fireworks Festival. This jawdropping spectacle began in 1733, after crop failure and a cholera epidemic killed thousands of people in the city during the previous year.

In order to commemorate and honor the souls of the deceased, General Tokugawa Yoshimume ordered a fireworks display be given during the Suijin (Water God) Matsuri. To this day, the Sumidagawa River Fireworks Festival remains one of the most popular in Tokyo, attracting around one million people every year.

However, if you’re looking for a festival that’s really associated with good health, then the Gion Matsuri in Kyoto is the answer. This festival’s roots go all the way back to 869. In those times, Kyoto had been hit hard with outbreaks of diseases such as cholera, dysentery and malaria. The ancient Japanese believed these illnesses to be the work of evil spirits. To make peace with these spirits and protect people from disease, a certain type of ritual, goryō-e, came to be. While it started out as a ritual performed whenever pestilence struck, it had become an annual event by the year 970, and the forerunner to the Gion Matsuri.

Over time, men carrying halberds in the ritual were joined by banners and umbrellas, which finally give way to elaborate yamaboko floats by the 14th century. In a display of true dedication, the procession has been taking place every year on July 17 for hundreds of years, come rain, sun, snow or even typhoon!

0

0