Discover the Tradition of Momijigari: Japan’s Autumn Leaf Viewing Custom

As the opaque summer skies turn a brilliant blue (akibare), harvests are reaped (minori-no-aki), and appetites return (shokuyoku-no-aki)1, a nation is fortified to welcome in a string of national holidays and traditional activities that take most people outdoors. Think busy weekends filled with sports days, school festivals, fund-raising bazaars, trips to visit the grandparents, and dressing children up in kimono to celebrate milestones2

Here, though, let’s pause for a breath and take a close look at a more leisurely autumn past time, one that everyone can enjoy: momiji-gari, or “hunting for fall colors.” Japan observers are familiar with hanami, or flower watching in the spring, when everyone goes out to enjoy a drink and a few chicken skewers under cherry blossoms. Cherry tree orchards are planned and planted, usually around schools and parks and other public spaces. When it comes to momiji-gari, on the other hand, a trip out of town and into the mountains is often the best way to see autumn foliage. Perhaps this is why the term is “hunting” rather than “watching”—it’s a longer trip that may require sturdy shoes, a Thermos of hot tea, and a hearty bento3 lunch of rice balls, pickles and karaage chicken, all wrapped and packed in a knapsack. The mood is introspective rather than raucous, and no one would look twice at a person enjoying the scene on their own.

The Art of Momijigari: Understanding the Cultural and Historical Roots of Japan’s Fall Tradition

Momiji is the name of the Japanese maple tree with its dainty leaves. Many different trees turn colors, but none are more spectacular than the momiji as it moves through several hues until it reaches the bright red it is synonymous with—literally. The original name of the tree was kaede, and it is still used, but as the leaves came to signal autumn, it began to be written using the same Chinese characters as koyo4, which means “colored leaves of autumn,” and pronounced as momiji. Eventually the word came into common use to refer to maple trees in all seasons. Momiji is a well-loved motif in Japanese culture, and can be found in just about all art forms, both classic and modern. It is also a “season word” in poetry.

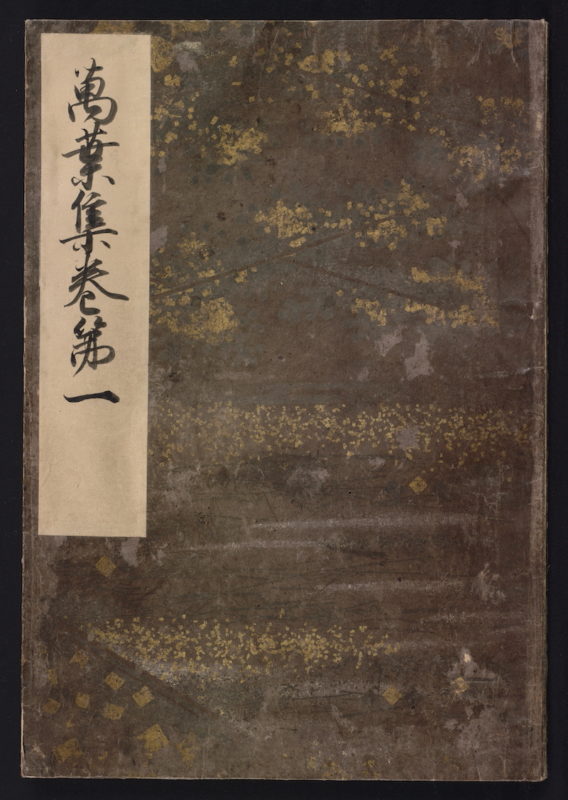

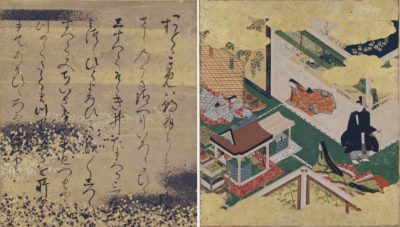

Enjoying the colors of fall dates back from before the Heian period (794–1185), when nobles at their leisure did nothing more exerting than “hunt” for autumn leaves, set up for a party and write poems. Such events can be found in both Manyo-shu, the classic book of poetry completed in the 8th century, and The Tale of Genji5, the famed 11th century novel about life in the Heian court. As with many other popular customs, Momiji-gari began to leave the confines of the nobility and spread among the burgeoning middle class during the Edo period (1603–1868)

Deborah Iwabuchi , a US-born Japanese-English translator based in Gunma, Japan, runs Minamimuki Translations (minamimuki.com) and teaches at Gunma Prefectural Women’s University. She works in many different fields, has translated dozens of books by Japanese writers—prominent and otherwise—and co-authored books in Japanese on learning English.

Notes

The heat and humidity of Japanese summers can have a devastating effect on energy and activity. The seasonal release into the dryer cool of autumn is described by a raft of vocabulary containing the word fall (aki). Among them akibare (the brilliant, blue fall sky), minori-no-aki (fall harvest—which can be applied to any other activity one succeeds at between September and November), shokuyoku-no-aki (the good appetite of fall, which comes after little desire to eat in summer), dokusho-no-aki (reading in fall—when the days are shorter and cooler, making it a perfect time to curl up with a book). Not to be forgotten are supotsu-no-aki and geijutsu-no-aki, fall of sports and art, respectively.

Shichi-go-san: November 15 is the official date of “Seven five three,” a coming-of-age event for children, but youngsters dressed up in kimono and other finery can be seen visiting shrines and posing for pictures for most of the month of November. Girls usually celebrate when they are three and seven, and boys at age five.

Shichi-go-san: November 15 is the official date of “Seven five three,” a coming-of-age event for children, but youngsters dressed up in kimono and other finery can be seen visiting shrines and posing for pictures for most of the month of November. Girls usually celebrate when they are three and seven, and boys at age five.

Bento: While Westerners may be more inclined to casually “brown bag it,” Japanese revel in their bento—usually translated as “boxed lunch.” Deceptively small in size, bento boxes usually contain a complete and balanced meal. The typical home-made feast contains rice with salty sprinkles, deep-fried bite-sized chicken (karaage), simmered and seasoned vegetables, a beautifully rolled omelet, a cherry tomato for color, and perhaps a bite or two of fruit in season. It is all beautifully arranged to encourage the appetite of the eater as well as to ensure them of the love of the person who made it.

Bento: While Westerners may be more inclined to casually “brown bag it,” Japanese revel in their bento—usually translated as “boxed lunch.” Deceptively small in size, bento boxes usually contain a complete and balanced meal. The typical home-made feast contains rice with salty sprinkles, deep-fried bite-sized chicken (karaage), simmered and seasoned vegetables, a beautifully rolled omelet, a cherry tomato for color, and perhaps a bite or two of fruit in season. It is all beautifully arranged to encourage the appetite of the eater as well as to ensure them of the love of the person who made it.

Chinese characters 紅葉: Written Japanese has two syllabary “alphabets,” but gets most of its context from Chinese characters or pictograms, which have uniform meanings, but can be combined in a variety of ways and pronounced in even more. Hence the combination of the characters for red 紅 and leaves 葉 can be pronounced both koyo (autumn colors) and momiji (maple).

The Tale of Genji by Murasaki Shikibu, a lady-in-waiting at the Heian court. Considered by many to be the world’s first novel—the plot of this vast work covers the life and loves of nobleman Hikaru Genji. The ancient book has been translated into modern English a number of times, making it perhaps more accessible in that language than in the original ancient Japanese.

0

0