Risshun, the Lunar New Year, means “beginning of spring,” although the early February weather is still quite cold. Next comes Shunbun, the spring equinox, when people in Japan begin searching in earnest for signs of the end of winter. Despite the appearance of delightful plum blossoms and other blooms and sprouts, however, there are still only sporadic warm days. Practically speaking, Shunbun signifies the end of the long nights of winter, with six months of increased daylight ahead.

The Role of Hachiju-hachiya in Japanese Agriculture and Seasonal Farming

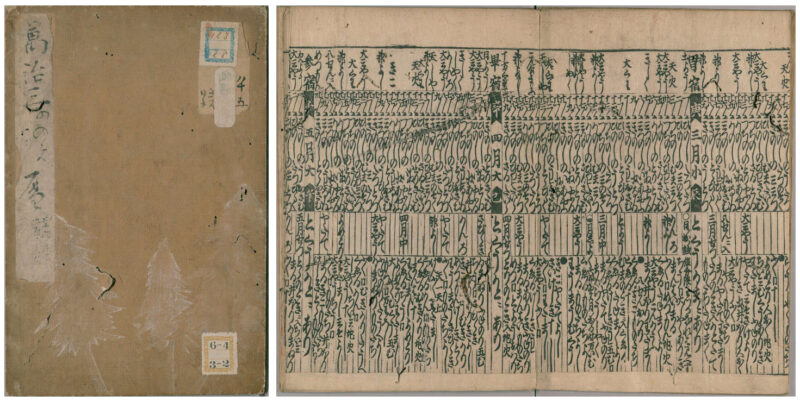

This is where Hachiju-hachiya, ”the 88th night” comes in. It falls on or about 2 May, eighty-eight days after Risshun. The first record of this date was in 1656, when it was included in Ise-goyomi, a sort of almanac published in the town surrounding Ise Shrine1 and distributed to the masses of visiting worshippers. This date had a very practical role in agriculture. Weather in early spring is fickle, but there are actually few instances of frost after May 2, and Hachiju-hachiya became a catchy way2 to notify Edo-era farmers that it was safe to plant rice seedlings as well as to harvest tea. The Japanese archipelago is long from north to south, and some northern areas have frost longer into the spring. Despite this variation, however, Hachiju-hachiya has been used for over four hundred years as a natural rule of thumb.

Shincha and Its Significance: The Freshness and Tradition of First Tea Leaves

Today, there are more scientific ways to farm, but Hachiju-hachiya is still widely used to kick off the tea harvest. Japanese prize the first of just about anything when its season rolls around, and this is also true for the very first tea leaves picked. Some of the leaves are quickly processed and sold as shincha (new tea) 3 during the first few weeks of May. Shincha made of leaves harvested on Hachiju-hachiya has a fresh and slightly astringrnt flavor, and is said to have special properties to keep ill health at bay for the coming year. Unfortunately, the rapid processing means its flavor is fleeting, so it is best when promptly brewed and consumed.

Along with a cup of shincha, you might enjoy a plate of hatsu-gatsuo 4, or “first bonito,” another first that Japanese have long prized, and which was immortalized in a haiku by poet Yamaguchi Sodo (1642–1716). He described the pleasures of late spring as green leaves, the mountain cuckoo and the first bonito. This fish swims north along the Pacific coast of Japan in the spring, looking for food after the long winter. The “first” catch off the western coast of Honshu corresponds nicely with the shincha season, and the taste of the fish is lean and fresh, delicious served as sashimi.

Spring is here, and we can enjoy the seasonal aspects of Japanese food and drink at home, even as we dream about where we’ll go when we get the chance!

Deborah Iwabuchi , a US-born Japanese-English translator based in Gunma, Japan, runs Minamimuki Translations (minamimuki.com) and teaches at Gunma Prefectural Women’s University. She works in many different fields, has translated dozens of books by Japanese writers—prominent and otherwise—and co-authored books in Japanese on learning English.

Notes

Ise Shrine in Mie Prefecture is the most important Shinto shrine in Japan; it is where the sun goddess Amaterasu is enshrined. The shrine has an official role in society, and members of the Imperial family participate in some of its annual rites. Today, many Japanese consider a pilgrimage to the shrine an important lifetime event, but during the Edo era (1603–1867) when Ise-goyomi was published, some estimates put the number of pilgrims at one out of every ten of the population, hundreds of thousands a year.

Hachi, or eight is considered a lucky number because the Chinese character for it is two lines that spread out at the ends (八). In Japanese, the description of this shape is the same as the expression for “have a long life.” Since multiples of lucky numbers are even better, the characters for 88 (八十八) are even more auspicious. This number denotes the actual number of days after the lunar New Year, but would have also been easy and pleasant for 17th-century farmers to remember.

There are two types of shincha, and they are frequently confused. The first is shincha described above and the second is also harvested at the same time. Both are made of the highest quality tea leaves, those that stay in the soil throughout the winter and absorb the most nutrients of any of the annual harvests. The difference between the two is in how they are processed. The second is roasted in the manner of succeeding harvests, much more slowly than the first, locking in a sweet and delicious flavor. This second new tea is not ready for sale until fall.

Bonito swim up the Japanese current to the northern end of Honshu, and then catch the Kuril back south beginning in about September. Bonito caught between September and November are called modori-gatsuo, or “returning bonito.” After feeding throughout the spring and summer, its flesh is now fatty and rich. The difference in flavor of hatsu-gatsuo and modori-gatsuo gives the impression of two completely different varieties of fish. Bonito has long been a staple in the Japanese diet. Most people these days are familiar with the term umami, but what you might not know is that one important source of the flavor is bonito. Dried and smoked into blocks, bonito is shaved into paper-thin slices (katsuo-bushi) and boiled to make dashi stock, the umami flavoring in misoshiru and other Japanese foods.

0

0